It has been four years since his wife died. On a glass table in their home, there are two framed photographs of her: one taken when she was a young woman, the other when she had matured into middle age. Among the pretty trinkets, there’s a small bottle of perfume she wore.

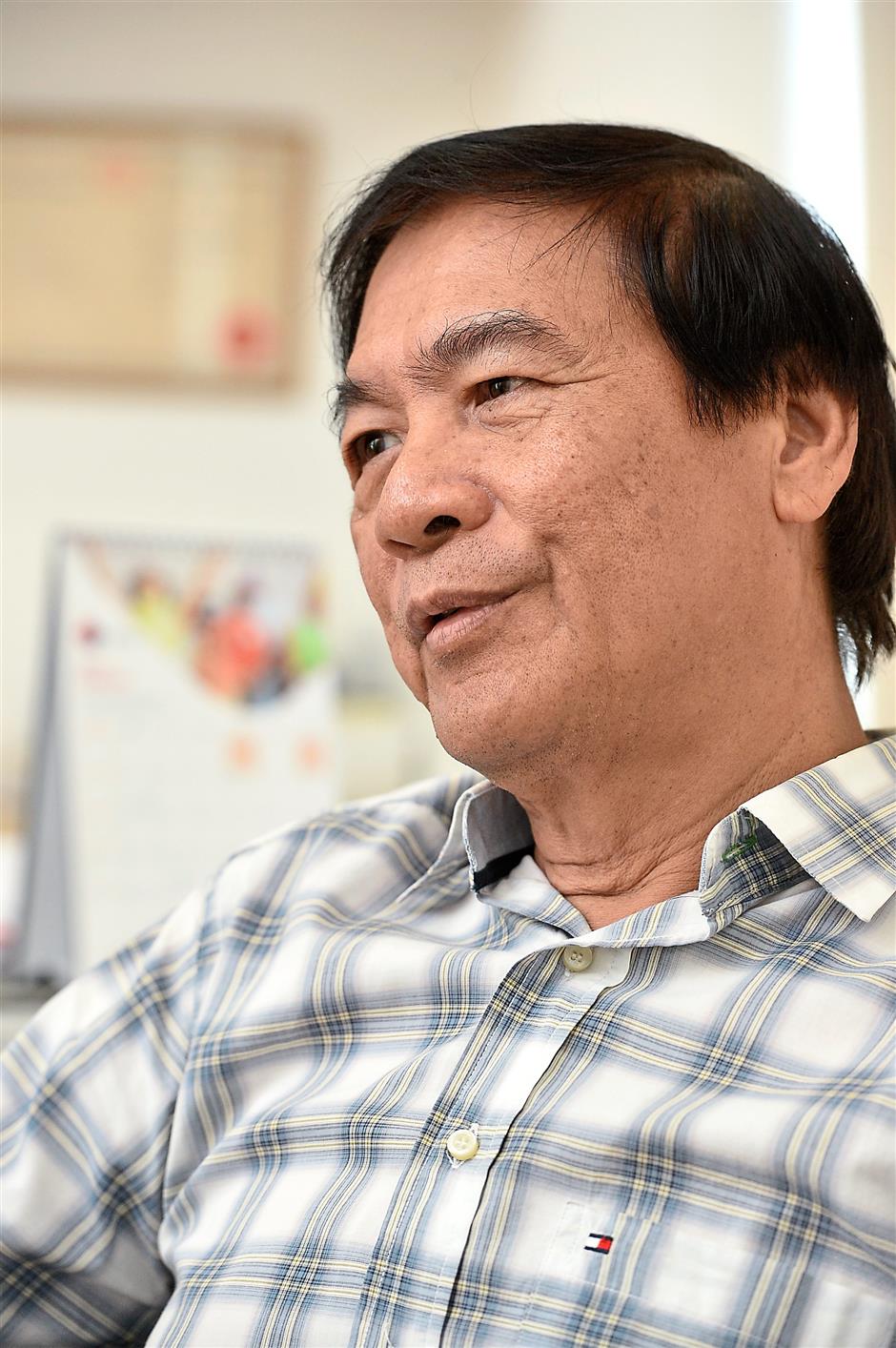

“It looks like a shrine, but it’s really not,” Richard Yeoh says. “The photographs were from her funeral, and some of the other things were given by friends.”

His late wife, Jennifer Young, was 55 when she was killed, struck down by a reckless taxi driver in Makati, the Philippines. Her husband, more than 2000km away in KL, was informed an hour later by phone.

“It was almost unbelievable, almost unreal,” Yeoh, 62, says. Behind his large, owlish glasses, his eyes glimmer with unshed tears. The memory is still raw, his grief still palpable.

“Fortunately, I had two of my boys with me. I broke the news to them. We were all in a state of shock, but after that we did whatever we had to do.” They travelled to the Philippines to recover her body, made funeral preparations and buried her.

“In those early days, I dreamt about her. I felt this helplessness. The sense of helplessness – you know you can’t do anything about it – is terrifying.” He pauses, blinks rapidly, then expels a long breath.

She may be gone, but her presence can be found in every part of the house. In the garden, there are potted plants she watered. In a closet in the living room, there are boxes of her shoes stacked high. Upstairs in their bedroom, there are her clothes, hanging limp and untouched.

“There was no chance to say goodbye. It just happened like that,” Yeoh says, snapping his fingers to underscore the suddenness of her death.

The retiree coped by going for grief counselling, confiding in close friends and pursuing his hobbies and interests. He drew strength from his spiritual faith. Underpinning his new life, his “new normal”, was total acceptance of what happened.

“I had to accept that loss is a part of life. I had to accept that that chapter of my life was closed, and a new chapter had opened. You have to carry on the best that you can.”

For a man who was married for 29 years, it was tough going at first, especially when it came to managing more prosaic tasks, like paying the bills and going to the market.

She had always handled “the admin” side of things, and he felt unmoored without her practical, level-headed efficiency.

But he learned. Out of the chaos, a new order established itself. Out of the ashes of their shared life, a new normalcy arose.

The glue that held everything together was their three sons – Jeremy, 32, Jonathan, 31, and Joshua, 27.

“They were as shocked as I was. I’m very close to them. When it happened, we cried together. We still talk openly about it. We talk about her; we share what we remember.”

“Although I’ve lost my spouse,” Yeoh says, he is comforted by the fact that “our family is still intact.”

Coping as a family

Jothy Rajoo’s husband has been dead for 14 years. He died of a heart attack at 43, leaving her and their four young children behind. Mark Silvanus was a pastor and a stern disciplinarian, the breadwinner and backbone of the family. In pictures, he is a stout, moon-faced man, wearing a wide grin that crinkles the corners of his eyes. When he died, their well-ordered lives were thrown into disorder.

“I didn’t expect him to die. The doctor said he could be discharged from the hospital on Monday, but he died on Saturday,” his widow says.

A housewife at the time, his death plunged her into panic and shock. He had left her with no savings. While the Yeoh children were adults when their mother died, the Silvanus kids were all under 11 when they lost their father.

“I had a hard time, but even though I was grieving, I knew I had to raise my kids,” Jothy, 56, reveals. The petite, plain-spoken woman threw all her energy into single motherhood, doing whatever she could to cobble together a life for her children. Needing to stay close to the kids, she peddled second-hand clothes in their apartment block. At the nearby pasar malam, she hawked whatever goods she could.

But money was always tight, their futures tenuous. Eldest child, Andrew, just 11 then, was the only child who understood the gravity of the situation.

“A few days before my father passed away, he told me – these were probably his last words to me – that I needed to take care of the family because I was the eldest son.”

Andrew, a carbon copy of his father in likeness and bearing, tried his best to support his mother and siblings. Once he left school, he got a job to supplement his mother’s income. The end goal was to work hard so his siblings could attend university and lift the family out of poverty.

Amanda, the youngest child, is 20, a university student with a shy, nervous smile. She doesn’t remember her father much; she was six when he died.

“When I was younger, I didn’t realise how hard my mother had to work. But as I grew up, I realised how hard it was for her,” she reflects.

“My mum consoled and supported me whenever I was down,” she says. “I never felt that my family was incomplete without my father, because my mother was everything.”

Fourteen years since the tragedy, Jothy has weathered the storms of widowhood.

She has raised her children well, and coped with the grief of losing a spouse so unexpectedly. But it’s her kids that she’s proudest of.

“When he first died, I suffered a lot, but now I’m happy with my life. My children are very good. They take care of me,” she says, beaming from ear to ear. “Everything is okay.”

Facing loss

For Yeoh and Jothy, life went on in spite of sudden bereavement. With the help of family and friends, they mourned, made adjustments and moved on. But accepting the finality of death and coping with a new set of circumstances are deeply unsettling. The newly widowed sometimes need professional help to manage the emotional wilderness of grief.

Dr Edmund Ng, a psychotherapist who specialises in handling grief, has been helping the bereaved deal with their loss for eight years. He founded Grace to Grieving Persons Outreach (GGP) in 2007. The grief care centre assists the grieving in coming to terms with their loss in a healthy way.

“Grief is a natural response to loss. Everybody will experience it. The problem is that people think they can swallow a pill and make it go away. But because it’s natural, it must be experienced and cannot be bypassed,” he says.

He cautions against avoiding grief by setting it aside because it’s too painful to deal with.

“One of the biggest challenges is facing the pain of the loss. Pain is unpleasant, so most people want to avoid it. But you have to deal with and confront grief. Once you’ve confronted it, it won’t come back to ‘bite’ you later on.”

Dr Ng says that the support of friends and family is vital. In the initial stages of the loss, they can help with practical affairs: providing domestic help, taking the children to school, making important phone calls and handling insurance matters.

Later on, they can lend shoulders to cry on and listen to the grieving as they process their loss.

As to whether there will ever be closure, it seems that it’s nothing more than a TV buzzword, bandied around but rarely exposed for the myth that it is. In truth, there is no full closure to grief.

“There is no such thing as full closure. While the bereaved will never forget the memories of the person that was once part of their lives, there will still be days, years down the road, when they re-experience the loss,” Dr Ng says.

“But if they understand grief,” he continues, “and grieve in a healthy way and as completely as possible, they can recover from the loss and move on in life with hope and resilience.”

It takes time to come to terms with the loss of a loved ones. Dr Ng offers some tips to deal with the grief.

1. Deal with your grief. Ignoring or bypassing your emotions will suppress your grief. The grief will remain in you until it gets triggered off at a later time. This is detrimental to your physical health and mental wellbeing.

2. Be kind to yourself. You are going through a very difficult season in your life. Do not push yourself to overcome your sadness. Give yourself the permission and space to grieve.

3. Embrace the pain. Do not fight the grief like it’s an unwelcome guest. The earlier you can accept your grief as a natural response to loss, the less miserable you will be. Just tell yourself the pain will be with you for some time.

4. Talk about your loss. Expressing your loss helps you to process the grief, vent your emotions, identify the issues within you that need to be resolved and reconstruct your meaning and purpose in life.

5. Receive support from others. Receiving help from others is not a sign of your weakness. Find people who can empathise with you and open up to them. Share your grief.