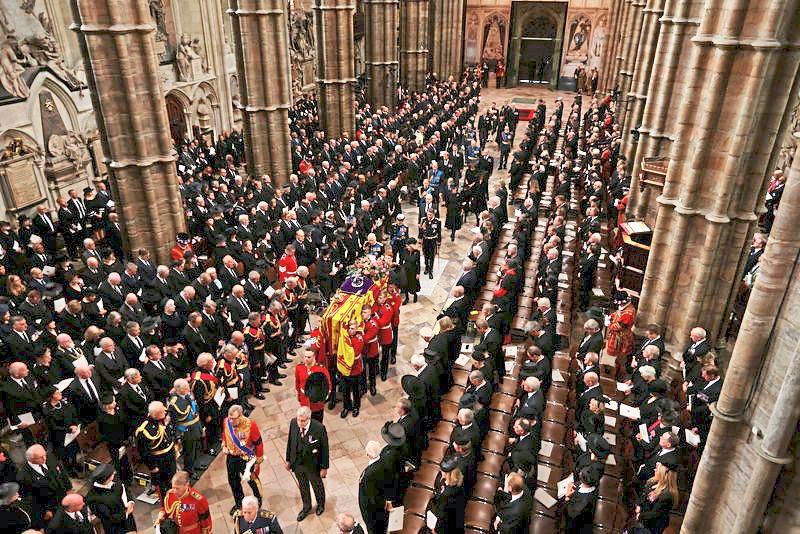

Queen Elizabeth II’s death was reported to have been communicated internally in one coded phrase: “London Bridge is down.”

It is said that from that moment, Buckingham Palace and the UK government set in motion meticulously-planned and coordinated procedures related to her funeral.

In fact, Queen Elizabeth had to approve the details of her funeral well in advance of her actual demise, therefore, planning would have taken place while she was alive and well.

Not many in this world will have the luxury of multiple stakeholders being involved in such methodical planning and execution of one’s funeral.

Although death itself is a natural part of life, many of us probably do not even want to think about it.

However, with all the media coverage of Queen Elizabeth’s passing, it may have spurred many Malaysians to think about what it means to die.

Such thoughts are not uncommon, especially when we grieve the death of a family member, a close friend, or even a pet.

Contemplating our mortality might seem like a distraction from reality, but the opposite may be true.

It can actually be grounding, as reflecting on our own death creates a context for our life.

While this may seem counterintuitive, there is evidence that keeping death at the forefront of our mind can have a positive influence on our psychological well-being.

Thinking about death gives us an opportunity to make adjustments to our life and to use the present to become the type of person we want to be.

Healthy awareness of death can clarify what really matters to us, as it can help us make decisions that align with our values.

Being conscious of the inevitability of death can make people less defensive about their world views and more selfless toward others.

This does not mean that we should be obsessed with our own mortality, but that contemplating the end of our life can help us live a healthy and fulfilling life in the here and now.

Accepting our mortality

Coming to terms with our mortality is a challenge faced by us all and accepting death can be hugely problematic.

We each have to find our own way to process the reality of dying, but faith can help, as can taking a practical approach.

For example, accepting that life has a finite span focuses the attention, enabling us to take stock of our lives and think about the possibilities still ahead.

Thinking about our life ending can be anxiety-provoking, so it is best to make time for periods of calm and contemplative reflection.

This time should help us see things more clearly, making it easier to take the necessary steps toward living the best version of our life.

Sister Anne Donockley, an Augustinian nun from Cumbria in the United Kingdom, once said: “I once saw something where it mentioned that on a coffin there are two dates: the date of your birth, the date of your death and there is a little dash in between the two – the hyphen.

“The most important of those three things on the coffin is actually the hyphen, representing your life between birth and death.”

Leaving a legacy

Accepting death, rather than running away from the thought or fearing it, can help us to make the most of our time-limited existence.

This drives the need to leave something behind after we are gone, thereby outliving and transcending death.

This could be a highly creative force.

The need for a legacy can be an important contributor to dealing effectively with the prospect of demise – lessening feelings of hopelessness and a lack of purpose.

Those who are interested in being remembered by future generations are also likely to take responsibility for their health and place value on their internal development.

The desire to provide a legacy that outlives us can be an excellent way to accomplish more in life.

When we face a haunting reminder of our death, focusing on what we would like to leave behind could help us turn something terrifying into a positive motivational experience.

Artists are the perfect example of this.

Through their creative legacies, they live on and are never totally gone.

Such legacies also help those who remain to cope with their loss.

No longer familiar

Another major issue with accepting death is that for the majority, the last moments of death are no longer something that we often witness firsthand.

As recently as the last (20th) century, death was everywhere.

A significant number of people died in childhood.

People usually died at home with their families, rather than in the hospital.

However, due to rapid improvements in public health, we rarely stare death in the face any more.

Most of us would like to die peacefully at home surrounded by our loved ones, but only a fraction are able to.

Sadly, a significant number may be admitted to the hospital before dying there.

As the process of someone close to us dying is no longer something that touches our day-to-day lives, accepting death becomes more difficult.

Denying death

In our country, some communities are more open about death, but in others, it is taboo to talk about it, particularly among older people with a more traditional cultural mindset.

It is not unknown for Malaysians to go to great lengths to avoid a certain digit or a particular colour that is perceived to represent death.

Too often, end-of-life planning only begins in the last few days of a person’s life – and only then if death is accepted as unavoidable.

By then, it may be too late for the dying person to choose where they want to die, who they want to be cared by, how to access the right sort of care to make all this happen to their satisfaction, and how they want to be sent off.

To make meaningful decisions about end-of-life care, people need to have an idea of what will be important to them as they reach the end of their lives.

This is difficult and confronting in a death-denying culture.

When they pass on, chaos may ensue as the family scrambles to make funeral arrangements, at times arguing on where the body should be buried or if cremation should be an option.

Settling the estate can become a nightmare, characterised by disputes on a variety of petty and often inconsequential issues.

People need to overcome their fear of advance planning.

It is not fair to place the burden of guessing our wishes on anyone else.

Planning should include executing a will.

Updating the beneficiaries may be an option, except in some circumstances where deceit may be suspected.

It will surely prove worthwhile to let the preferred final arrangements be known to close family members, just as Queen Elizabeth did.

The prospect of death is often scary, but it can also have positive effects.

Coming to terms with the fact that we have a finite amount of time on earth can provide a sense of spiritual peace, and enable us to maximise control over our life and strengthen our relationships with loved ones.

Datuk Dr Andrew Mohanraj is a consultant psychiatrist, the Malaysian Mental Health Association president and an adjunct professor of psychiatry at Taylor’s University. For more information, email starhealth@thestar.com.my.

The information provided is for educational and communication purposes only, and it should not be construed as personal medical advice. The Star does not give any warranty on accuracy, completeness, functionality, usefulness or other assurances as to the content appearing in this column.

The Star disclaims all responsibility for any losses, damage to property or personal injury suffered directly or indirectly from reliance on such information.

This article was first published by The Star Online on Oct 4, 2022.